Unearthing the past: harnessing history in the study of gemmology

by Dr. L.E. Cartier, first published in Facette 28 (May 2023)

Gemstones have been used in jewellery for millennia, with their history dating back to ancient civilizations. From Egypt to Mesopotamia, India to China, Europe and the Americas, gemstones have held deep cultural significance and have been treasured for their inherent beauty and mystical properties. In ancient times, gemstones were often associated with spiritual and healing powers, and were used for protection, worship, and adornment.

In ancient Egypt, gemstones such as turquoise, lapis lazuli, and carnelian were used in jewellery to symbolize protection and divine connection. The pharaohs and elite members of society adorned themselves with intricately crafted jewellery, often featuring precious gemstones. Gemstones were also used in burial rituals, with the belief that they would accompany the deceased into the afterlife. In ancient Mesopotamia, gemstones like carnelian and lapis lazuli were used in jewellery as amulets to ward off evil spirits and promote good fortune.

When Alexander the Great conquered the Persian empire in 331 B.C., his domain extended from Greece to Asia Minor, Egypt, the Near East, and India. This unprecedented contact with distant cultures not only spread Greek styles across the known world, but also exposed Greek art and artists to new and exotic influences and materials (including gemstones such as garnets).

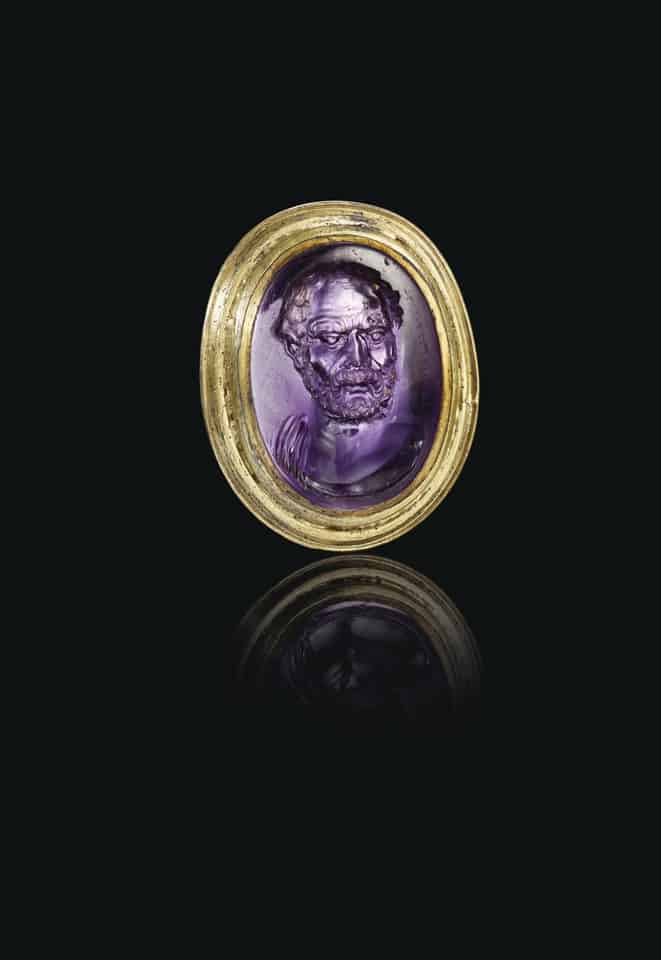

Romans in particular, adorned themselves with jewellery featuring colourful gemstones and pearls, and it was also common to have gemstones carved into intricate cameos or intaglios (Figure 1), which were used as decorative elements in jewellery. The Roman Empire (27 B.C. – 476 A.D.) was important in gem trading, jewellery manufacturing and new jewellery fashion. The Byzantine Empire, with its capital in Constantinople, persisted as a continuation of the Roman Empire in the eastern provinces throughout late antiquity and the Early Middle Ages and had rulers who treasured many different varieties of gemstones (Figure 2).

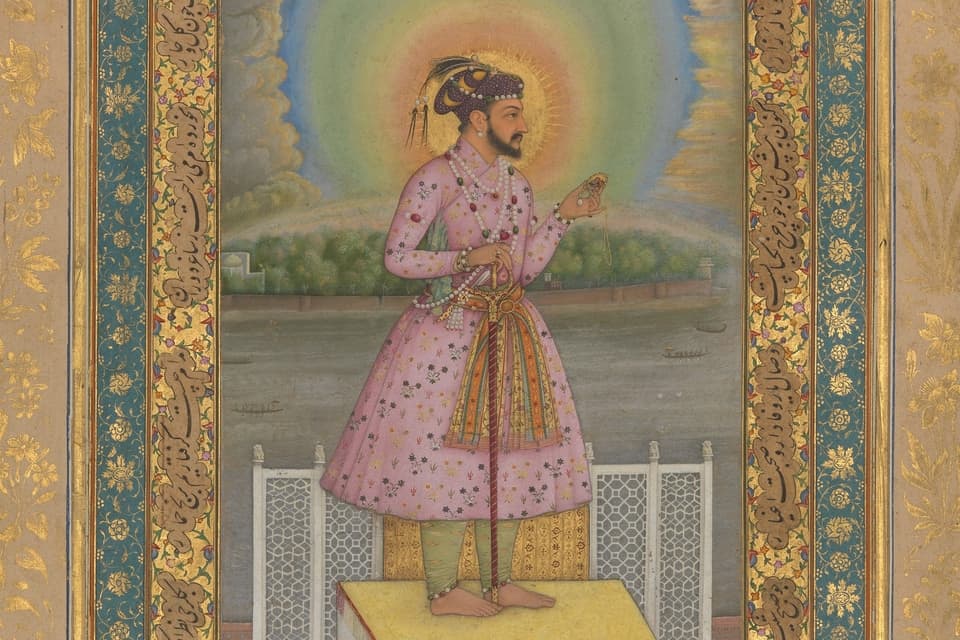

During the Renaissance period in Europe, gemstones regained popularity in jewellery as a symbol of wealth, power, and status. Royals and aristocrats commissioned exquisite jewellery pieces adorned with pearls, diamonds, rubies, emeralds, and sapphires, showcasing the opulence and refinement of the wearer. Many of the finest emeralds found in Colombia were traded and sold to the Mughal Empire during the 17th century (Figure 3). In India, gemstones were and still are an integral part of traditional jewellery, believed to bring luck, prosperity, and protection to the wearer.

In modern times, gemstones continue to be prized for their beauty, rarity, and sentimental value. From engagement rings to statement necklaces, earrings to bracelets, gemstones are used in a wide array of jewellery designs, catering to various tastes and styles. With their rich history and enduring allure, gemstones continue to captivate and fascinate jewellery enthusiasts around the world. Throughout history, the availability, rarity, and desirability of gemstones have influenced jewellery design trends. Equally, it is interesting to study gem treatments and imitations over time as a means of better understanding developments in the global gem industry. Ultimately, the need to identify imitations, treatments, synthetics and cultured pearls led to the emergence of the field of gemmology.

Gemstone sources and their influence on jewellery designs: the example of diamonds

In India, diamond was for thousands of years known as a mark of power and religion. Diamond was also highly regarded as a symbol of strength and wisdom in Buddhism. The Ratnapariksha of Buddhabhatta, a 6th-century Sanskrit lapidary treatise states: “[The one] who wears a diamond is protected against all dangers, be it by serpents, fire, poison, sickness, thieves, or evil spirits.” India, and to a lesser extent Borneo, were the only source of diamonds until about 1730, when Brazilian deposits were discovered.

The legends and the mysticism connected to diamonds were appreciated during the Roman Empire (Ogden, 2018). With its fall, and the rise of Christianity in Europe, the situation changed and the appreciation for diamonds was greatly reduced for several centuries. Another reason was the rise of Persia and Islam. As Middle Eastern states gained control over much of the trade with India, their rulers, who had a taste for lavish ornaments, took control of many of the larger and more attractive diamonds coming from India.

As the fear of being accused of heresy and facing persecution diminished in Christian Europe, there was an increased recognition of the virtues of diamonds, and a greater openness to incorporating ideas from classical and Eastern traditions. Beginning in the 14th century, diamonds began to exert their power in the new Western culture of the Renaissance.

Venice became the first European diamond centre from the 13th to the 16th century, as it was at its time one of the most important markets for all kinds of goods from the Orient. At that time, most diamonds reached Venice by the silk route through Persia and Arabia. Diamond trading in Europe later moved to Lisbon and Antwerp which were important sea powers at the time (Ogden, 2018).

In the 18th century, when the Indian diamond mines declined, new and important diamond deposits were found in Brazil. After 1860, Brazilian diamond production rapidly declined, resulting in a great shortage of rough diamonds in the European cutting centres. Fortunately, diamonds were discovered in South Africa in 1870.

The Belle Époque jewellery period (ca. 1870-1914, see Figure 3) could not have thrived as it did without the discovery of diamond deposits in South Africa after 1870- there simply would not have been enough diamonds to supply the growing demand for diamonds during that period. Additionally, the discovery in 1906 of important platinum deposits in South Africa meant that this metal could be more widely used in jewellery at that time. These two examples exemplify well how designs and trends are also influenced by whether a gemstone is available in sufficient supply or not.

While coloured stones such as sapphires (often used by royalty during the Middle Ages) remained very popular, other stones became more sought-after during and after the Renaissance. There were no ruby mines in Europe however, so royals depended on traders coming back from the East to bring back Sri Lankan and Burmese rubies. It was difficult for explorers to reach the famed Mogok ruby mines in Burma, and many historic rubies were in fact spinels. Long reserved to royalty due to scarce supply, rubies became more used in jewellery during the 20th and 21st century as new mines were discovered on the African and Asian continents.

On the other hand, the arrival of the Spanish in South America marked a big change for emerald and pearl supply in the 16th century. When the Spanish arrived in Colombia and reached Muzo in 1543/1544, intense mining activity over the following decades would produce large quantities of emeralds that would be exported to Europe and Asia (Lane, 2010). Similarly, when Christopher Columbus and others discovered pearls in Central and South America, this generated great wealth for the Spanish crown and triggered what is known as the “Pearl Age” among European royals and aristocrats who were able to source much greater quantities of high-quality natural pearls (Figure 5) (Bari & Lam, 2010).

Imitations and treatments in history

“To tell the truth, there is no fraud or deceit in the world which yields greater gain and pro t than that of counterfeiting gems” Pliny the Elder (Roman naturalist, A.D. 23/24 – 79)

Gemstones have been treated for thousands of years, with evidence of gemstone treatment techniques and imitating gems dating back to ancient civilizations such as the Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans. The practice of treating gemstones to enhance their appearance or properties can be traced back to at least 4,000 years ago (Nassau, 1984). These treatments were often used to improve the colour, clarity, and durability of gemstones or to imitate more valuable gemstones. It is said that the Roman Emperor Diocletian in about 300 A.D. ordered all books describing the fabrication of artificial stones to be burned because this had become a major issue (Nassau, 1984).

The treatment of emeralds using oil, for example, is nothing new. First reports from Pliny and in the Stockholm Papyrus (supposedly written 400 B.C.) suggested “Smaragdi (emeralds) improve with undiluted wine and green oil, however much they have been naturally stained.” (Barney et al., 2006).

One more recent (18th century) example of an imitation is rhinestone, also known as strass. It is a type of imitation gemstone that is created to resemble a diamond and is typically made from materials such as quartz, glass, or plastic (Figure 6). The term “strass” is derived from the name of Georg F. Strass (1701-1783), an Alsatian jeweller who was known for his imitations of diamonds as seen in Figure 6.

Another example is fossilized dentine, also known as odontolite, which has been historically used as a turquoise imitation. Since medieval times, French Cistercian monks have used a heating process to turn the material light blue which they thought to be turquoise. These ‘stones’ were originally set in medieval religious artefacts, but came again into fashion in the early to mid-19th century as can be seen in the set of six antique brooches in Figure 7 (see also Krzemnicki et al., 2011).

The use of gemstone treatments and gem imitations has continued throughout history and is still widely practiced in the modern gemstone industry. However, it is important to note that the disclosure of any gemstone treatments is now required to ensure transparency and consumer protection.

The quest to synthetize gem materials

There have been many theories over the centuries over how gems form, and perhaps also of how humans could synthetize them. Theophrastus (about 315 B.C.) believed that “(precious) stones are produced by solidification from fluids, some through the action of heat others of cold” (Caley, 1956). John Mandeville in 1360 suggested that “a diamond is synthesized when two larger ones, one male and one female, come together, in the hills where the gold is. And the diamond grows larger in the dew of a May morning”. We know today that diamonds can be synthesized using CVD and HPHT techniques.

The history of synthesizing gem materials dates back to the early 19th century when scientists and jewellers began experimenting with various chemical and physical processes. One of the earliest successful attempts was the synthesis of ruby, which was achieved by French chemist Auguste Verneuil. In 1885 a dealer in Geneva began to sell “Geneva ruby” that is now believed to have been created by flame fusion, the process that Verneuil and others were developing at the time (Nassau, 1969). This was before Verneuil’s 1902 announcement of being able to synthesize rubies. It was likely linked to previous work by Frémy and others in Paris. By 1907, several manufacturers were producing synthetic ruby at a rate of 5 million carats per year (Nassau, 1980). This important new supply of synthetic ruby at the turn of the century means that jewels from that period may occasionally contain such stones (Figure 8).

The emergence of gemmology

Gemmology has its roots in ancient times when humans first began to appreciate the beauty and rarity of gemstones. However, it was not until the 19th century that gemmology as a formal scientific discipline began to emerge.

In the early 1800s, with the rise of scientific disciplines and technological advancements, gemstones started to be studied more systematically. Mineralogists and geologists began to analyse and classify gem materials based on their physical and chemical properties. Pioneering scientists, such as James Dwight Dana, Nils Gustaf Nordenskiöld, and George Frederick Kunz, made significant contributions to the field of mineralogy and gemmology, laying the foundation for the scientific study of gemstones.

The challenges the trade experienced with distinguishing natural and synthetic rubies, and natural and cultured pearls planted the seeds of gemmological research. Whilst it was first thought that UV-light could distinguish natural and cultured pearls in 1921, this turned out to be wrong. By 1927, X-rays and endoscopes were being used to identify cultured pearls (Ogden, 2012). These developments led to the formation of the first gemmological laboratories and gemmology journals that focused on detailed research of gem materials.

New sources of gemstones

The 20th century saw significant discoveries of new gem sources and gem varieties (Figure 9), which has provided jewellery designers with exciting new materials to work with, and for gemmologists to study.

The appeal of garnets changed significantly when demantoid garnets were discovered in the Ural Mountains of Russia in 1853. These beautiful and brilliant green gems were widely used by jewellers including Fabergé in St. Petersburg. It was popular in Russia in the period 1875-1920 and in Edwardian jewellery (1901-1915) and continues to be a rare gem used in jewellery today. Tsavorite, the green vanadium-bearing variety of grossular garnet was discovered in 1967 by Scottish geologist Campbell Bridges. He sold his first stones of pure green colour to Tiffany’s, who named this new gemstone after Tsavo National Park in Southern Kenya, close to where Bridges had originally discovered it. Tanzanite is another new gemstone variety discovered in the region in the late 1960s.

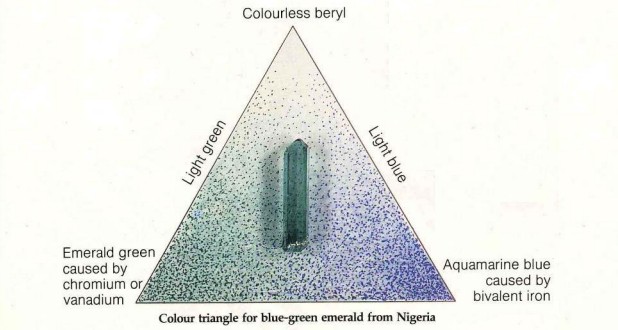

In the late 1980s, a new type of tourmaline was discovered near Sao José da Batalha in the State of Paraíba, Brazil. This copper-bearing material excels by its vibrant blue to green colour and became known as Paraíba tourmaline; it is considered today one of the most rare and valuable varieties of tourmaline. Similar material would later be discovered in Mozambique and Nigeria.

These and other discoveries have provided designers with access to either previously unknown gem materials or a greater supply of existing gemstones (e.g. Mozambique for rubies, Madagascar for sapphires), allowing them to create unique and innovative designs. The discovery of new gem sources and gem varieties will continue to have a profound impact on the world of jewellery design in future, providing designers with a wealth of new materials to inspire their creativity and elevate their designs to new heights of beauty and artistry.

To learn more about the history of gemstones and jewellery take our ATC Gems & Jewellery course.

The course explores the different uses of gems through history, and how these link with different periods of jewellery design. Through this approach, students learn about criteria to identify historic jewellery that contains gems, and gain insights into possible criteria for valuation. Students also learn about fakes and imitations through time, and criteria to identify these. This course is taught in small groups, and will includes extensive workshops, discussions and practical work.